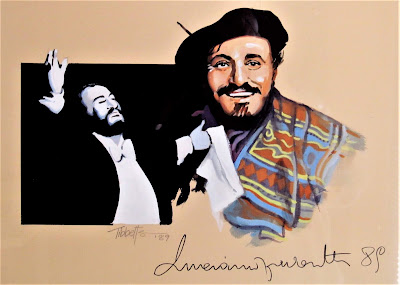

THE FOLLOWING INTERVIEW ARTICLE WITH LUCIANO PAVAROTTI BY JOHN C. TIBBETTS WAS FIRST PUBLISHED IN “THE CHRISTIAN SCIENCE MONITOR” ON 5 May 1989. I RECALL THESE EVENTS NOW UPON RECENTLY VIEWING THE NEW RON HOWARD DOCUMENTARY.

MY 1989 INTERVIEW FOLLOWS BELOW IN ITS ENTIRETY.

I suppose not many folks can say they spent a half hour alone with opera superstar Luciano Pavarotti in the backseat of a limousine...

Let me explain:

OPERA superstar Luciano Pavarotti has received many extravagant titles over the years, from ”The King of the High C's'' to “Grandissimo Pavarotti.'' But perhaps none is as close to his heart as the simple appellation, “Doc.'' “Doctor Pavarotti'' is the way he is known to the citizens of the town of Liberty, Mo., just a half hour's drive from Kansas City.

Mr. Pavarotti has just arrived at the Kansas City airport in preparation for a solo concert recital next Tuesday under the auspices of Richard Harriman and William Jewell College.

It is a warm spring evening, but he has the familiar red silk scarf wrapped about his neck. He is trimmer than I expected. We exchange hurried greetings and move to his curbside limousine for a prearranged interview.

Once inside, the flashing cameras and the noises are shut out. Luciano settles back into the deep cushions with a sigh. He is tired. The evening before, he had just finished preparing Verdi's “Luisa Miller'' with the prizewinners of the latest Pavarotti International Voice Competition in Philadelphia. Ahead in coming weeks are performances at the Metropolitan Opera and a European tour.

“Yes,'' he continues, “I just finished `Elixir of Love,' and there is a recording of `Trovatore' ahead, and then the tour - but after that I go to my beach house at Pesaro [on the Adriatic coast] for the rest of the summer....''

He pauses a moment, checking the slim, leatherbound notebook he carries in the inside pocket of his jacket. The solo recital Tuesday is the only such concert he will give all season. Indeed, the recital will mark the fifth time since 1973 that he has come here under the auspices of the William Jewell College Fine Arts Series. He is looking forward to seeing many old friends.

“I think this recital is very important to everybody,'' he explains, “since the first time I made my first recital was exactly in this place.''

His face is etched in silver outlines by the lights outside the car window. The voice that can fill auditoriums the size of Radio City Music Hall and Madison Square Garden is hushed in this tiny cell of silence.

“That recital gave to my performing a different dimension,'' he says. “I was able, through this first concert and the others that follow it, to reach people who were not the usual people for the world of the opera. Some go only to see opera; others only to the recitals. Now I find both. Yes, it all start here from the Liberty, Mo., concert.''

It had been a chilly February night when Pavarotti first came here to perform sixteen years ago. At that time he was known in the music world solely as an opera performer.

The young man, born in Modena in northern Italy, had given up careers as an elementary school teacher and nighttime insurance salesman to pursue singing. He moved quickly from his opera debut near his home town in 1961 in “La Boheme'' to a debut four years later at La Scala in Milan (again in “La Boheme'') and then his Metropolitan Opera debut in 1972 as Tonio in Donizetti's “La Fille du Regiment.''

In the audience at that Metropolitan debut was Richard Harriman, an English professor from William Jewell College, and supervisor of the college's concert series. Professor Harriman decided he would try to get this young singer to appear at the college in a recital.

When he contacted Pavarotti's press representative, Herbert Breslin, he was told the singer did not do recitals, but possibly they could kick around the idea. “So we talked further,'' Harriman recalls. “It developed that Mr. Pavarotti had considered a solo recital debut, but it would cost me $6,000. Now in those days, that was the fee given to the highest-paid tenor in the world, Richard Tucker. `Nobody's ever heard of your singer,' I said. After a pause, his voice came back to me: `They will!'''

Soon the arrangements were made, but when Pavarotti arrived the night before the recital he was unsure that he would be well enough to go on. The next day, however, he felt better. “I got the call from Mr. Breslin that all was well,'' says Harriman. “We made the drive into Kansas City, where Mr. Pavarotti was staying at the Muehleback Hotel. He warmed up on the piano in the Presidential Suite, which once belonged to President Harry S. Truman. We bundled him up and got him back to campus, and the rest is history.''

What Pavarotti remembers about the concert was his nervousness about appearing on stage alone. “I was very nervous where I'm going to put these hands,'' he says. “So I decided to stuff my hand with a handkerchief, and during the performance my hand began to move normally. From that day I considered it a very good-luck concert for me, because it began something very new for me.''

In a later conversation with me, his accompanist, John Wustman, talked about the concerts here. Pavarotti “was so used to the opera stage, and he felt naked,'' Mr. Wustman said. “There was no prop, no glass, none of the things you might have in `Rigoletto' or any other opera. I think he felt he needed something, and this [handkerchief] idea came to him. It has been his trademark ever since, the world over.''

Wustman was not Pavarotti's pianist that night. He started accompanying Pavarotti at the singer's third concert here, in 1978. “But it is the fourth time I remember the best,'' said Wustman. “That was in September 1983. We moved the concert from the William Jewell campus in Liberty to nearby Kansas City. That was a special time for Luciano.”

Make that “Doctor'' Pavarotti.

That was the year the singer received an honorary PhD in music from the college. The ceremony was packed with spectators, opera fans, and local and national news media. Pavarotti beamed in his cap and gown as he walked to the podium alongside his sponsor, Professor Harriman.

Now, as the William Jewell Fine Arts Series celebrates the opening of its 25th season, it seems only fitting that Doc Pavarotti return for another benefit.

The singer lifts his shoulders in a quiet shrug when I ask him how he managed to be here. He is not one to dwell on such things. “I fit it in, yes. I am glad to come here again. It is really something to be able to come here and make real a piece of music in this way - when you are alone on the stage with nothing else - nothing, just a fantastic pianist like I have.'' There is a knock at the limousine window. The luggage has arrived and has been stowed in the trunk. Time to leave.

One wonders if the quiet simplicity of this area reminds him of his native village of Modena and the soccer fields of his youth. Or maybe it's just the way folks talk to him here. After all, there are times - even in the life of an opera superstar - when the simple title of “Doc'' is preferable to “Grandissimo.”