|

|

Tom Hardy in MAD MAX FURY ROAD

|

“HOW THE HELL DID HE DO THAT?” is my first response to MAD MAX: FURY ROAD. “HE” refers not to the redoubtable Max but to veteran Australian filmmaker George Miller, who started the whole saga of Max Rockatansky back in the late 1970s. And “HE” also refers to ace cameraman John Seale, who began his career with other Aussies, notably Peter Weir, and is not only FURY ROAD’s cinematographer but the camera operator as well.

Together, Miller and Seale have wrought a masterpiece of aeronautical engineering. FURY ROAD may be a stunt, but it’s an airborne stunt that fills the screen with flying trucks, plummeting oil tankers, leaping motorcycles, and, of course, Max himself.

|

|

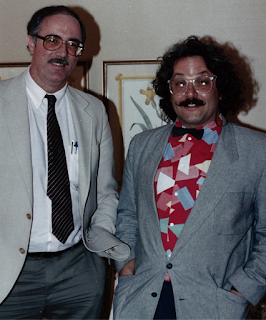

George Miller in 1982

|

It may be more than thirty years since Miller decided to put away his physician’s stethoscope and strap cameras to fast cars (see the photo above), but the man, on the evidence of this film hasn’t faltered his stride. Indeed, he’s grown wings.

While some critics are trashing the film and others are offering their own hosannahs, let’s talk about George Miller. I interviewed Miller several times back in the day when MAD MAX, THE ROAD WARRIOR, and MAD MAX BEYOND THUNDERDOME first hit the accelerator. Those interviews now appear in my forthcoming book, Those Who Made It: Speaking with the Legends of Hollywood (original title: Hollywood Speaks!) Here are some excerpts from Miller’s rather droll take on the havoc he has unleashed:

GEORGE MILLER: I came to the film industry pretty late. I was a medical graduate and working as a resident in a hospital when my brother and I won a film competition, and we went to a workshop at Melbourne University. That was in 1970. I always had been a film buff, and when I met Byron Kennedy there, I started dividing my time working in a hospital and experimenting on film with him. We both literally slept, ate, and thought movies. Nothing else mattered. Byron and I made a short satire called Violence in the Cinema, Part I. We showed it at the Sydney Film Festival and it was picked up for distribution. I didn’t even know what “distribution” meant! I think the best thing about having done medicine was that it kept me away from making films for so long. I had time to mature, to see the world. As a doctor I was accustomed to seeing patients in fairly extreme states. I had to grapple with that and confront things I would not otherwise have done.Miller was quick to downplay his ambitions. Just remember that this is also the man who went on to make the sublime LORENZO’S OIL and the daffy BABE: PIG IN THE CITY:

I have never been a “highbrow” kind of person. I have always preferred pop arts, comic books, that sort of thing. And so I have always loved chase films—like those classic films with Buster Keaton and Harold Lloyd. I think they’re pure visual language. Keaton, particularly, understood the syntax of film so well. And car-crash culture has always fascinated me. Where I worked in the hospital, I had my own morbid fascination with what I call “autocide”—deaths on the highways from car crashes. I’d see so many young people killed, or maimed for life, on the roads.

|

|

Mel Gibson in 1982. Original title: MAD MAX II

|

|

| Me and the original "Mad Max," Mel Gibson, taken in 1985 |

Instead of guns and swordfights of American and Samuarai movies, we use the car chases as rituals of death. Personally, I can’t stand slow films. I actually think our first Mad Max was too slow! Now, Road Warrior feels violent, but if you really look at it frame by frame, there’s only the ambiance of violence. Byron and I have studied lots of stunt and chase movies. We’d put them on the editing bench and realize that the cars didn’t really do all that much—it was done through cuts and speeding up bits of film and slowing them down and intercutting them with cutaways to a screaming face, or something. You won’t actually see many frames of explicit violence. But what I hope is that Mad Max II has the kind of kinetic push that doesn’t give you much time to rest. Chases are among the purest forms of cinema.

The American troubadour poet and film critic, Vachel Lindsay proclaimed as much back in his 1915 treatise, The Art of the Moving Picture. George Miller is his latter-day heir.

I want people to come out of the movie feeling like they’ve been on a roller-coaster ride. I feel good when I come out of movie exhausted! And I love to move the camera!